Blog Listing

- @Number71

- Before We Go blog

- Best Fantasy Books HQ

- Book Reporter

- Bookworm Blues

- Charlotte's Library

- Civilian Reader

- CrimeReads

- Critical Mass

- Dark Wolf's Fantasy Reviews

- Everything is Nice

- FanFiAddict

- Fantasy & SciFi Lovin' News & Reviews

- Fantasy Cafe

- Fantasy Faction

- Fantasy Literature

- Gold Not Glittering

- GoodKindles

- Grimdark Magazine

- Hellnotes

- io9

- Jabberwock

- Jeff VanderMeer

- King of the Nerds

- Layers of Thought

- Lynn's Book Blog

- Neth Space

- Novel Notions

- Only The Best Science Fiction & Fantasy

- Pat's Fantasy Hotlist

- Pyr-O-Mania

- Reactor Mag

- Realms Of My Mind

- Rob's Blog O' Stuff

- Rockstarlit Bookasylum

- SciFiChick.com

- SFF Insiders

- Smorgasbord Fantasia

- Speculative Book Review

- Stainless Steel Droppings

- Tez Says

- The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.

- The B&N Sci-Fi & Fantasy Blog

- The Bibliosanctum

- The Fantasy Hive

- The Fantasy Inn

- The Nocturnal Library

- The OF Blog

- The Qwillery

- The Reading Stray

- The Speculative Scotsman

- The Vinciolo Journal

- The Wertzone

- Thoughts Stained With Ink

- Val's Random Comments

- Voyager Books

- Walker of Worlds

- Whatever

- Whispers & Wonder

Blog Archive

-

▼

2013

(259)

-

▼

March

(23)

- Three Recent SFF Books of Interest, Steven Amsterd...

- "Quintessence" by David Walton (Reviewed by Liviu ...

- No Return by Zachary Jernigan (Reviewed by Mihir W...

- “River of Stars” by Guy Gavriel Kay (Reviewed by C...

- GUEST POST: Word of Mouth: Or Just Let Me Be Read ...

- “The Raven Boys” by Maggie Stiefvater (Reviewed by...

- “Etiquette & Espionage” by Gail Carriger (Reviewed...

- “Cloud Atlas” by David Mitchell (Book/Movie Review...

- Winner of the “River of Stars” Giveaway!!!

- "Shadow of Freedom" by David Weber (Reviewed by Li...

- GUEST POST: Writing Wuxia As Chinese Historical Fa...

- NEWS: Ilona Andrews' New Series, Michael J Sulliva...

- "Where Tigers Are at Home" by Jean-Marie Blas de R...

- “Impulse” by Steven Gould (Reviewed by Casey Blair)

- “Scarlet” by Marissa Meyer (Reviewed by Lydia Robe...

- “The Indigo Spell” by Richelle Mead (Reviewed by C...

- GUEST POST: The Legend of Vanx Malic & Other News ...

- The Grim Company by Luke Scull (Reviewed by Mihir ...

- WORLDWIDE GIVEAWAY: Win a SIGNED HARDCOVER COPY of...

- GUEST POST: The Debut Novel: A Series of Intention...

- "On the Edge" by Markus Werner (Reviewed by Liviu ...

- NEWS: Ides Of March Giveaway, Gord Rollo's The Jig...

- “Written In Red” by Anne Bishop (Reviewed by Casey...

-

▼

March

(23)

Wednesday, March 13, 2013

GUEST POST: Writing Wuxia As Chinese Historical Fantasy by Albert A. Dalia

In A Genre Writer’s Notebook blog titled “Writing Historical Fiction: Traveling the Tang Dynasty” (3/31/2012), I wrote:

So my first journeys in writing were as a historian, a nonfiction writer. In those travels, medieval China looked like thousands of ancient Chinese characters, interpreted by thousands of Japanese characters, further interpreted by thousands of English words…my travels through historical texts were both exciting and imaginative. I’ve always loved history and its study has always been like travel for me. When I read history, especially historical documents or see objects created in some historical period, I become a time traveler. Perhaps, what I didn’t realize when I was reading as a historian was that imagination played a much larger role than I recognized...

When I added travel over the earth to my travels over the page and arrived in East Asia, my journeys through medieval China began to add the elements of sensual recognition. The sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile sensations of China began to influence my travel perspective. With these additions, my historical travel became more exciting, more imaginative, and more adventurous. Researching the social and intellectual history of the medieval Chinese Buddhist clergy, I was now able to go out and meet them – or at least, their lineal descendants. A doorway, or, perhaps a rabbit hole, had opened. I could not only learn their point of view on their own history, but could also begin to see first hand their perspective on the world around us. As I became better at spoken Chinese, I learned more and more about these different perspectives. As a result of living in a Chinese Buddhist monastery for a year, I not only got to see how it functioned internally, within itself, but also how it functioned within its society.

Perhaps it was the accumulation of all these factors – sights, smells, tastes, sounds, tactile sensations, and new acquaintances – that moved me from traveling through medieval China as a historian, thinking I was seeing the “reality” of that time and place, to discovering a deeper form of travel – that of the fiction writer.

As I noted in my previous guest post, my travels as a fiction writer have been in a particular Chinese genre: wuxia shenguai. I loosely translate this genre title as “heroic fantasy.” But wuxia (武俠) commonly translated as “martial arts fiction,” has both a long history in China and, with anything that old, a number of specific attributes.

I sum these attributes up in an information article that I wrote for my students:

The wuxia genre is a traditional Chinese storytelling form defined by two basic elements: wu and xia. Wu pertains to all things martial such as weapons (especially the sword as a symbol of nobility and valor), fighting techniques, and martial culture. Xia is usually translated as “chivalric hero.” Xia refers to those men and women who acted in a subjective, heroic manner to right injustice. Their sense/code/ethic of chivalry involved the following values: altruism, justice/appropriateness, individual freedom, personal loyalty, honor & fame, generosity & contempt for wealth, and reciprocity.

This genre normally focuses on action (especially the action of the human form) and adventure and takes place in an imaginary world of these heroes known as the jiang-hu (literally, “rivers and lakes” also “cultural-imaginary world”) which has been defined as, “the self-contained and historically sanctioned world of martial arts.” It is a world that accepts the fantastic as normal at certain levels of skillful physical and mental attainment.

An important motif of this genre is a sense of nostalgia for a lost home in a mythical past that lacked any confusion about moral values – good and evil were simple and clear. This genre can further be developed as a subgenre of historical fiction. When treated as such, it should, “polish the past into a mirror of the present.”

From my perspective as a wuxia writer, the xia ideal is about friendship. It is perhaps the most profound sense of friendship – for the xia are willing to give their lives for strangers just recently befriended, for ideals that resonated within their hearts, and for a sense of higher attainment in whatever path they followed. The friendship ideal embodied by the xia represents one of the most profound and moving human ideals. Perhaps, it is at the core of what really makes us human.

If you find this interesting and would like to know more about the Chinese history of this genre, there is a long article on my Genre Writer’s Notebook blog, “A Brief Outline of the Xia (swordsman/women hero) in Chinese Literature up to the 9th Century C.E.” Further, a few more words about the idea of shenguai (神怪), mentioned in my previous guest post might be useful here. My sense of this term has evolved into an appreciation for the great Chinese short story writer, Pu Songling (1640-1715 C.E.) who composed the famous Liaozhaizhiyi (Strange Tales from the Liaozhai Studio) collection of tales of the fantastic or Strange. As Judith T. Zeitlin (Historian of the Strange: Pu Songling and the Chinese Classical Tale), one of the leading scholars on Pu Songling, explains:

It was clearly recognized in China that the strangeness of a thing depended not on the thing itself but on the subjective perception of its beholder or interpreter. The strange is thus a cultural construct created and constantly renewed through writing and reading; moreover, it is a psychological effect produced through literary or artistic means. In this sense, the concept of the strange differs from our notions of the supernatural, fantastic, or marvelous, all of which are to some extent predicated on the impossibility of a narrated event in the lived world outside the text. This opposition between the possible and the impossible has been the basis of most contemporary Western theories of the fantastic…”

Specifically referring to Pu Songling’s work, she continues:

But the rules are different in Liaozhai. Ghosts can be accepted as both psychologically induced and materially present, just as a sequence can be cast simultaneously as a dream and as a real event…the strange often results when things are paradoxically affirmed and denied at the same time. In other words, the boundary between the strange and the normal is never fixed but is constantly altered, blurred, erased, multiplied or redefined. In fact, the power of the strange is sustained only because such boundaries can be endlessly manipulated.

It is this sense of the Strange that I seek in my wuxiashenguai historical fantasy genre. But before I get too carried away by my lingering bad habit of academic exposition, let’s get back to my fiction.

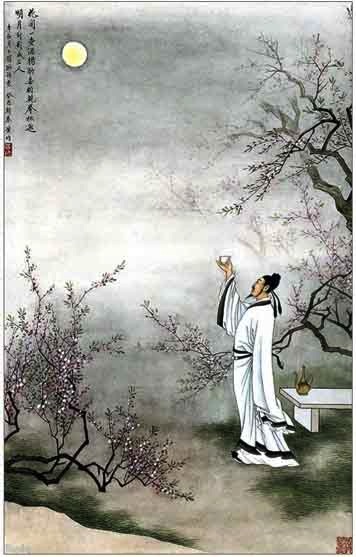

My first novel-length medieval China historical fantasy was Dream of the Dragon Pool: A Daoist Quest. As is my writing pattern, I pick a historical character and develop a story around that character. In this case it was one of China’s greatest poet’s Li Bo (李白, also read as Li Bai, 701-762 C.E.). A poet as a swordsman? While we have a lot of his poetry, we only have a dim outline of Li Bo’s life. There are a lot of stories – one of which has him claiming that in his late teens he lived with a Daoist master who taught him swordsmanship and that he killed a couple of people in sword fights. That was enough for me! Combine that with the fact that he was charged with treason and exiled to distant Burma via the Yangtze River and I had a river trip as my plot. That’s where the shenguai aspect enters, as Li Bo discovers an ancient, powerful sword, the Dragon Pool Sword, which attracts a number of fantastic antagonists.

My story finds Li Bo near the end of his life, exiled from the Tang Court, suffering a form of writer’s block – he can no longer compose poetry, and an outsider on many levels. The historical Li Bo’s murky background also suggests that he was not an ethnic Chinese. What evidence that can be found seems to point to a far Western ethnic family origin – perhaps, Persian, as in Iran. So I used this to make him a stranger in his own land, a stranger who had mastered the native language so that he was one of the preeminent poets of his time. There were many at Court that resented this “foreigner” who so fluently and eloquently expressed the deepest human emotions in their mother tongue.

All travelers need partners, so I paired Li Bo with a fictitious Central Asian warrior, Ah Wu, who had fought in many of the Tang dynasty wars of conquest along the Silk Road. Their relationship was based on a poem spontaneously composed by a drunken Li Bo (he’s famous/infamous for his drinking) to the Emperor that saved Ah Wu’s life. The latter, in true wuxia style, pledged his life to Li Bo. The trip up the Yangtze River involves mystery, swordsmanship, ghostly enchantments, humor, and heartbreak. But this is a “Daoist Quest” so it is unlikely to end like some sort of Greek quest! Some readers have asked if there is a sequel. Yes (the outline exists). Someday...

My next novel, Listening to Rain, is the first in a trilogy. This time the historic figure is a 7th century Buddhist warrior monk, Tanzong (曇宗). We have a beiwen (stele) dating from that period that was discovered at the Shaolin Monastery. It commends and awards thirteen Shaolin monks for their contribution to Li Shihmin’s (599-649 C.E.; Emperor Taizong r. 626-649 C.E.) successful efforts to unite the Chinese empire and establish the Tang dynasty (618–907 C.E.). Their leader, Tanzong, was granted the military rank of “general-in-chief.” This is all we know of these warrior monks.

Since, historically, we don’t know anything about him beyond what’s on the stele, I set Tanzong’s tale in that historic quest to unify the Chinese empire. This time directly influenced by the twenty volumes of Patrick O’Brian’s great historical fiction Aubrey-Maturin Napoleonic sea warfare series, I give Tanzong a “Maturin-like” companion the Imperial Commissioner, Li Wei. While he is a fictional character, his master, the great Tang chief minister and advisor to the emperor, Wei Zheng (580-643 C.E.) was a major Tang historical figure. I also gave Li Wei the background of being the lead complier of the Tang imperial encyclopedia of “existing knowledge,” which allows him to know a lot of things. Yet, as a young man in his 20s, he doesn’t have the experience to “season” his knowledge. This gets him into a number of interesting situations as the pair travel through the dangerous far southern reaches of the shattered Chinese empire.

(Tang Emperor Taizong, r. 626-649 C.E.)

The antagonists of the trilogy, the Celestial Masters Daoist cult are still in existence in modern day China. They rose at the collapse of the Han dynasty in the third century C.E. and sought to unify China under their spiritual tutelage. Thus, in the overall scheme of things, the trilogy follows the broad outline of early Tang dynasty history.

The first volume, Listening to Rain, mostly takes place on contemporary Hainan Island, which is the map I’m standing next to in my author’s picture (see below). My finger is placed on the secret base of the female aborigine pirate, Byung Nhak.

The second volume, as yet without a confirmed title, takes place in Sichuan, mostly on Qingcheng Mountain outside of present day Chengdu. The mountain holds an important legendary significance for the development of religious Daoism in Chinese history.

While the third volume, also without a title so far, takes place on the Tibetan plateau in a little known region between the then Tang empire and that of the Tibetan kingdom, which was a potent medieval rival in the Central Asian region.

What happens after the trilogy could end up being the “secret scrolls” of Tanzong’s adventures, since the trilogy is supposedly written by Li Wei to record his public travels with Tanzong. The Silk Road to India beckons since at this very moment in Tang history the great Buddhist monk traveler, Xuanzang (602-664 C.E.) is moving through Sichuan heading out along the Silk Road to India; perhaps he needs a fellow-monk traveling companion or bodyguard! Further, I’m very much entranced with several of my female characters and would love to write spinoff novels about their adventures: the swordswoman White Rainbow and the pirate captain Byung Nhak.

Of course, time is always a problem in such endeavors since I do have a “day job.” Nonetheless, my intention is to develop my own style of this genre, as is natural for any writer in their chosen genre. I hope to do this by combining the various storytelling influences I’ve been exposed to as both a historian and as a student of various forms of storytelling: the written word, cinema, and audio. A few examples being: the wuxia movies I’ve been enjoying since the late 60s; the ideas about the Strange put forth in Pu Songling’s great collection of Strange stories (my short story collection, Strange Tales from the Dragon Gate Inn is dedicated to him); the great historical fiction of Patrick O’Brian; Latin American magic realism fiction; the various martial art masters I’ve studied under; and the several hundred biographies of Tang dynasty monks that I translated with their amazing shenguai sense all get mixed into the “inkpot” that serves my take on the wuxiashenguai genre.

This genre has survived so long because it's such a malleable storytelling form. One only needs to view its modern literary and cinematic history to understand this and appreciate the changes the genre has successfully gone through. I have no clue as to what will come out of all this, but then the fun of writing is in the discovery. I do hope you will all join me on this voyage of discovery!

Order the book HERE

Read The Reality Of Historical Fantasy (guest post) by Albert A. Dalia

Read Fantasy Book Critic's review of Listening To Rain

AUTHOR INFORMATION: Albert A. Dalia was born and brought in New York state. Growing up the author loved fast cars and coincidentally discovered Chinese culture. The author graduated from State University of New York majoring in History and Political Science and later studied Classical Chinese and Classical Buddhist Chinese literary languages at the National Taiwan Normal University, Mandarin Training Center in Taipei. Since then he's gotten two Masters and a PhD as well. He has also held a variety of jobs like broadcast journalist, assignment editor; copywriter for an ad agency, editor-in-chief, Associate Professor, Editorial director, etc. He currently lives nearby Boston with his family.

NOTE: Author picture courtesy of the author himself. All other character pictures courtesy of Albert A. Dalia.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments: